“I can’t explain miracles. There’s only one man I know who can. His name is Gideon Fell…”1

One of my current reading goals is a chronological readthrough of John Dickson Carr’s 23 novels featuring amateur detective and lexicographer Dr Gideon Fell. In a previous post, I shared my highlights from the first 10 books, up to The Black Spectacles (aka The Problem of the Green Capsule). I can now add a further three Fell mysteries to my Have-Been-Read pile, all of which were very enjoyable: The Problem of the Wire Cage (1939), The Man Who Could Not Shudder (1940), and The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941).

With these books, we enter the World War II era. The Case of the Constant Suicides is actually set in wartime (though “it was only the first of September [1940], and the heavy raiding of London had not yet begun.”) Carr went on to produce a further two Gideon Fell novels before peace was declared.

Here are my reflections on these three Fell excursions…

“Suppose you actually were going to commit a murder — how would you do it?” That was the question posed by Frank Dorrance, when a thunderstorm brought an end to the evening’s tennis match. Shortly afterwards, Frank himself is found murdered, his body lying in the middle of the tennis court. His fiancé Brenda White discovers the corpse, leaving an unfortunate trail of footprints — unfortunate because there are no other footprints on the wet ground, except the victim’s. But if Brenda is not guilty, who is? And how did they avoid leaving footprints?

Brenda turns to the real love of her life, Hugh Rowland, to deliver her from this predicament. Unsurprisingly, Hugh’s attempts to divert suspicion away from Brenda muddy the waters for the official investigators, Superintendent Hadley and Dr Fell. This creates an entertaining situation, where as a reader we have a very different perspective from Hadley and Fell. Perhaps some readers will be disappointed by the comparatively minor role Fell has in this novel, but I think Carr’s use of Hugh and Brenda is effective.

The tension between characters is captured well from the beginning. On the opening page, we're told: “Possibly because the day was sultry, emotions were growing sultry too”. The plot moves at a good pace, with terse chapter headings punctuating the narrative (“Love”, “Hate”, “Indulgence”, “Murder”, “Doubt”…). This book is also a good example of Carr playing with the reader by teasing multiple other possible explanations, before exposing each in turn as false.

There are a few less enjoyable aspects. The solution to the wire cage murder is not Carr’s finest moment, although it's the kind of outrageous scenario that Carr can get away with. There is also another disappointing moment towards the end of the novel, which Carr himself was not happy with, but included to indulge the demands of the publisher. In correspondence with Anthony Boucher, he described this scene as “not only bad, but unethical and lousy.”2 I won't include spoilers here, but if you've read the book, I think you'll know what Carr is referring to.

Even with these weaknesses, though, The Wire Cage is a fun mystery, with an interesting structure and an intriguing mystery. As a final aside, this book includes the final mention of the elusive Mrs Fell until Panic in Box C in 1966.3 The couple have recently moved from their flat at 1 Adelphi Terrace, which had been demolished “to make room for new blocks of offices whose polished pegs were not the place to support Dr. Fell’s shabby shovel-hat.” They now reside in a house in Hampstead, which has a garden with “room enough to play croquet in case any sane person should feel an inclination for that extraordinary pastime.”

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (4/5)

“A haunted house?”

Those are the tantalising opening words of The Man Who Could Not Shudder, where a conversation in a gentleman’s club introduces us to the sinister history of Longwood House. Martin Clarke, intrigued by the house’s backstory, decides to buy the property and invite a selection of guests to a little “ghost party” — a psychological experiment to see how they fare in the eerie atmosphere. Unsurprisingly, since this is a murder mystery, at least one of them will not fare particularly well.

The resulting plot has a good selection of spooky and bizarre ingredients, even if Carr could have arguably made more of the potentially threatening atmosphere. Within the first few pages, we get told about an elderly butler swinging from a chandelier that then crushed him. There’s an alleged spectre who likes grabbing people’s ankles, and a grandfather clock that mysteriously resumes its ticking after a long silence. And then there’s the murderous pistol, which jumps off the wall and fires a fatal shot, seemingly of its own accord.

After introducing all these elements, Carr leads us through a well-paced and engaging investigation. The mystery is fairly-clued, with some good misdirection. The solution is not Carr’s most satisfying, but it was a fun journey getting there. Perhaps the main weakness of this novel is the characters. Despite the intriguing setup, I found them all fairly forgettable — but, to be fair, Carr more than made up for that with the next book in the series (see below).

The book’s title is inspired by a Brothers Grimm fairytale, which happened to be G. K. Chesterton’s favourite.4 “The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was” (aka “The Boy Who Could Not Shudder”) is about a boy who wants to learn how to shudder. That story also has some ghostly goings-on, including a church sexton who pretends to be a ghost in order to scare the aforementioned boy. The boy wasn’t actually scared, but decided to push the sexton down some stairs, breaking his leg in the process.

As a final note, it’s worth mentioning that this book could have been lost to history if the Nazis had got their way. In September 1940, John Dickson Carr moved into a new home in London, which was hit during an air raid while Carr was reading a book in the living room. After this escape from danger, he moved to the Savage Club in London — but this also ended up being bombed by the Luftwaffe. His proofs for The Man Who Could Not Shudder were in the Club at the time. Thankfully, they were rescued from the ruins and this enjoyable novel survived.5 Read it, and defy the Nazis.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (4/5)

There are two types of people in this world: those who believe the first Duchess of Cleveland’s hair was auburn, and those who believe it was jet black. Dr Alan Campbell is very firmly in the latter camp, as we discover in the opening scene at a train station. Campbell is about to travel to Scotland for a family conference, where he will not be the only person with strong views on the Duchess of Cleveland's hair. Nor is the debate restricted to family — even Dr Fell can't help wading into it.

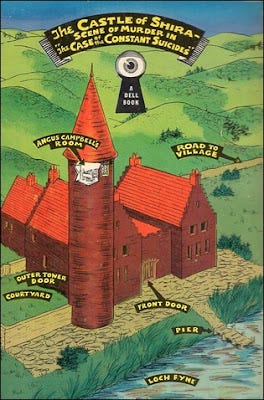

The family conference is not really about the Duchess of Cleveland's hair, though. It instead concerns a less significant matter: the death of Angus Campbell, who has fallen to his death from a locked room in a castle tower. Alistair Duncan, the family’s lawyer, and Walter Chapman, from the Hercules Insurance Company, are both anxious to answer the question: Was it suicide, accident or murder? Angus Campbell isn't the only dead body by the time they get an answer, and the “murder or suicide?” question will come up again and again.

The end result is one of my favourite Dr Fell mysteries so far, which offers a delicious combination of mystery and humour. The mystery itself is well-plotted and moves at a good pace. Carr provides you with more than one impossibly mysterious death to get your teeth into, with some good clues to look back on when the solution is revealed. I also enjoyed how the wartime setting was incorporated into the mystery, with some significant discussions around blackout curtains, lights and Home Guard patrols.

There is also a good stream of humour that runs throughout the book, particularly around character interactions and misunderstandings. This begins in the opening chapter, which has become one of my favourite openings of any detective novel. It continues as Alan Campbell arrives in Scotland and encounters a selection of comic characters, who are forced together in this unfortunate situation. There are also some wonderful descriptive lines, including of Dr Fell’s appearance: “Many more chins appeared as his amusement increased.” Some of the humour might be less welcomed by Scottish readers, but as a resident of Wales I didn’t mind.

Importantly, the comedic elements don’t overwhelm the actual puzzle. This is a genuinely good mystery, and a very entertaining one. Though I’m still not sure what colour hair the Duchess of Cleveland had.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5/5)

I’m just about on track to finish my Dr Fell readthrough by the end of 2025. Although I’m anticipating the quality to drop later in the year, I’m looking forward to my next few reads, which are generally highly-rated: The Seat of the Scornful (1941), Till Death Do Us Part (1944) and He Who Whispers (1946). Check back in May/June to see what I made of them!

From The Problem of the Wire Cage.

Douglas Greene, John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles (Otto Penzler, 1995), page 182.

S. T. Joshi, John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study (University of Wisconsin, 1991), page 86.

Douglas Greene, John Dickson Carr, page 263.

Douglas Greene, John Dickson Carr, page 245.

I am in the minority of John Dickson Carr fans who do not enjoy his playing around with supernatural themes. Which is probably why Wire Cage is one of my favourites. I agree that the solution is something only Carr could have pulled off but he did leave clues. And I thoroughly enjoyed the non-Gothic, commonplace setting of a country house tennis party!