We can obviously all agree that the 1930s was the best decade for the writing of crime fiction. But I occasionally enjoy exploring more recent offerings, especially books that either draw inspiration from the Golden Age Detective tradition, or subvert the usual plot expectations for crime fiction. Recently, courtesy of Bridgend Library Services, I’ve been delighted by two books from the last few years. I hope this post will be an encouragement to read them and/or visit your local library.

Everyone in My Family Has Killed Someone (2022)

“Everyone in my family has killed someone. Some of us, the high achievers, have killed more than once.” With his opening sentence, Benjamin Stevenson provides a deceptively simple summary of this novel’s premise — which proves to be far cleverer and more compelling than it first appears.

The plot unfolds in two main timelines. The main plot involves a family reunion at a ski resort, where a corpse soon turns up in the snow. Alongside this, there’s a gradually revealed family backstory, involving a shooting at a petrol station, an abduction, and several dead bodies. And in case you’ve forgotten, everyone in the family has killed someone.

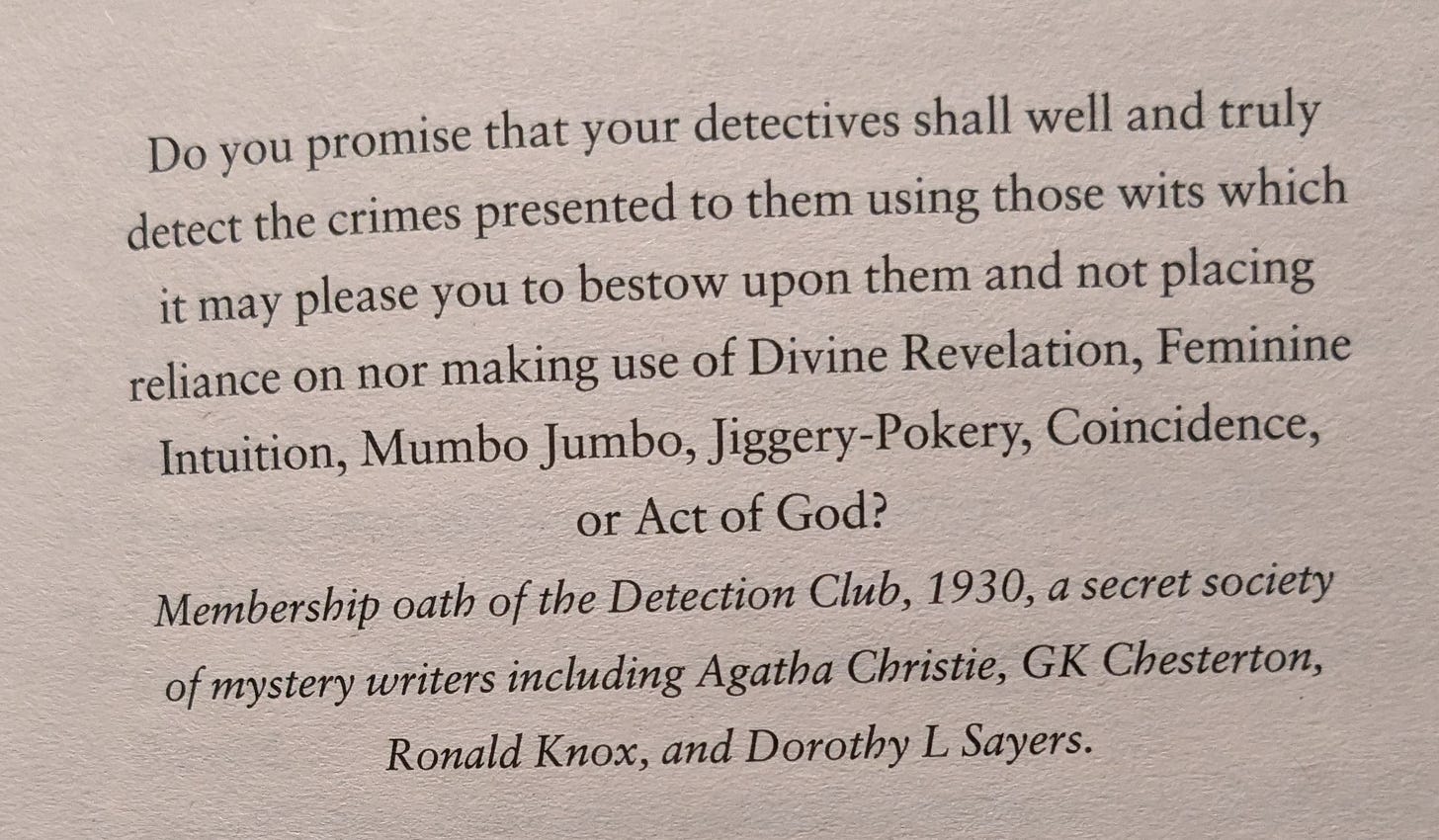

The real joy of this book is the narrator, Ernest Cunningham, who is wryly self-aware and absurdly honest (as well as providing some excellent one-liners).1 Before the book begins, we are reminded of Ronald Knox’s “10 Commandments of Detective Fiction” from 1929.2 Ernest then demonstrates his credibility credentials on page 2, where he provides a list of the page numbers where a death will happen and also mentions there is “one plot-hole you could drive a truck through.” Throughout the book, he regularly refers back to all of these elements, as well as deliberately drawing attention to clues (“I may as well put it in bold”). I realise some readers may find his narration grating. I found it completely brilliant.

Of course, Ernest’s earnest openness is still cleverly designed to mislead — and even the structure of the book itself is part of the deception. There is an interesting reflection later in the book, on the implications of mystery novels being physical objects:

I’ve always believed that there are more clues in a mystery novel than just what’s on the page. A book is a physical object, after all, which can betray a few secrets the author does not intend: the placement of section breaks; blank pages; chapter headings… If you don’t know what I’m talking about, think about the book in your hands. If a killer is ever revealed with more than a leaflet of pages remaining against your right thumb, they cannot be the real killer; there is simply too much of the book still to be read… A good author must not only wrong-foot the reader within the narrative, they must do it within the form of the novel itself. There are clues baked into the very object.3

There are lots of surprises in store for the reader, and Benjamin Stevenson keeps outwitting your attempts to work out what it means for every family member to be a killer. I also enjoyed the way small details re-appear as being significant later in the novel. This book is now a trilogy, and I’m definitely excited about reading the others.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5/5)

Murder Your Employer (2023)

If you like piña coladas and getting caught in the rain, you may well like this recent crime book from the writer of that song, Rupert Holmes.

The plot revolves around the McMasters Conservatory for the Applied Arts, where students are instructed in the art of homicide (euphemistically referred to as “deletions”). We follow the experiences of three aspiring deletists from the 1950s, as they learn their craft and then leave McMasters to put their learning into practice.

In one sense, this is not a serious book. The premise is absurd and the prose is filled with puns and dry humour.4 At the same time, it’s a very clever book. Rupert Holmes somehow makes the ridiculous setting seem plausible, and he uses different character perspectives and narrators in an effective way. The unusual set-up means it’s difficult to predict what will happen as the story unfolds, and there were a good number of surprises along the way.

I also enjoyed the exploration of the school’s unique system of ethics, where deletions are only justified if a student can correctly answer these four questions:

Is this murder necessary?

Have you given your target every last chance to redeem themselves?

What innocent person might suffer by your actions?

Will this deletion improve the life of others?

These moral criteria become more important as the book progresses, and Holmes cleverly makes you question where your sympathies lie as a reader.5

The main weakness of the book is, sadly, it doesn’t know when to end.6 Rupert Holmes attempts to bring everything together neatly, but I think a more abrupt ending would have worked better. The final chapter is especially disappointing. But the journey there was very very enjoyable, so I didn’t mind too much. An absorbingly quirky read.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5/5)

“Lucy runs an independent online business, by which I mean she loses money on the internet periodically.”

If you’re not familiar with these commandments, formulated to describe a pure form of Golden Age detection, you can read them here: https://www.writingclasses.com/toolbox/tips-masters/ronald-knox-10-commandments-of-detective-fiction.

This isn’t true in the same way, of course, with eBooks. But most of this book can be equally enjoyed in both physical and digital formats.

“Come along, Mr. Iverson, you must be starved to death,” said the dean. He saw my startled look and added dryly, “That’s an observation, by the way. Not a decree.”

For avoidance of doubt, I still believe murder is bad.

This is also arguably true of his 1979 song about piña coladas.