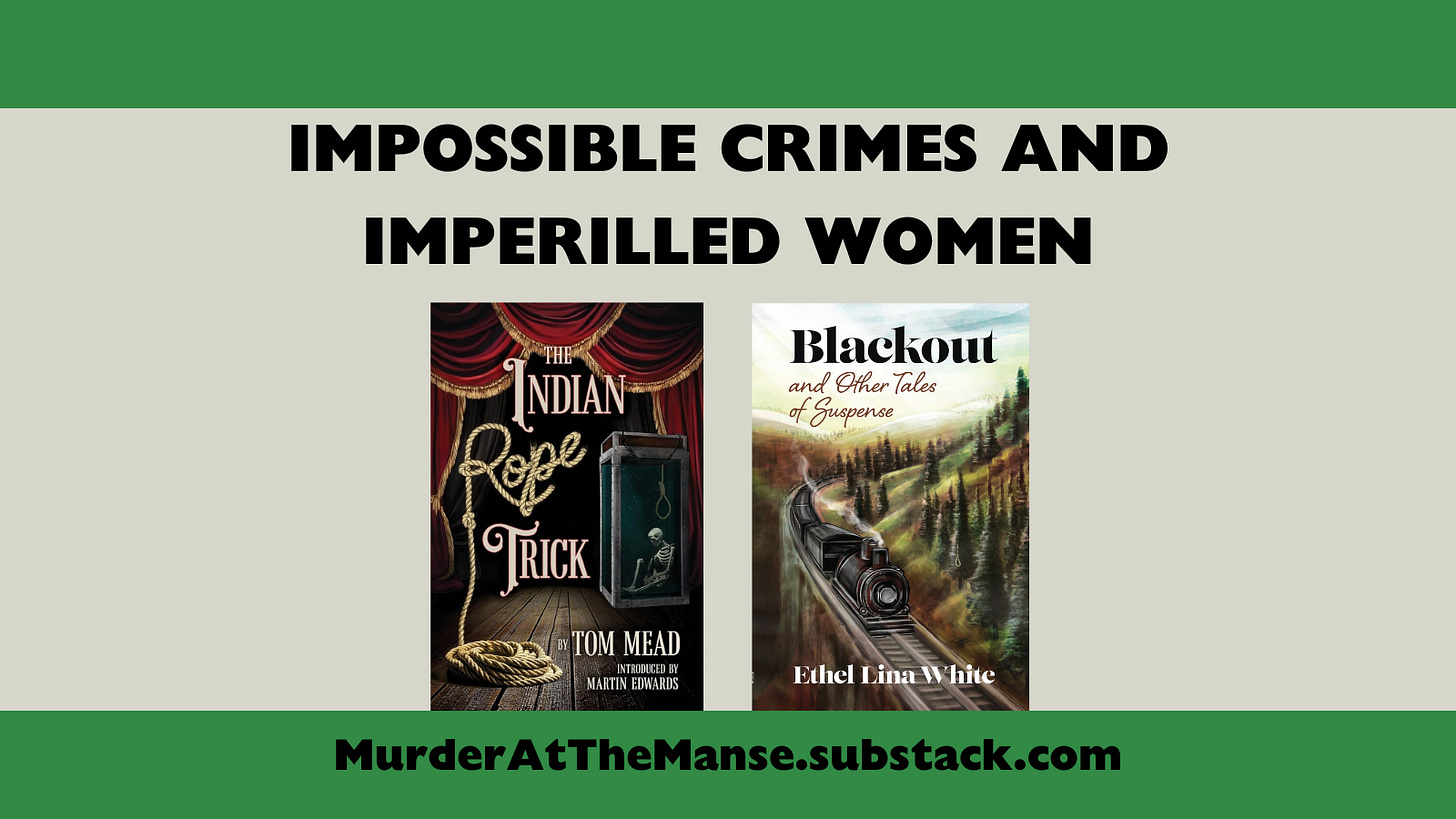

What do Tom Mead and Ethel Lina White have in common? I can think of at least three things:

They’ve both spent time in Abergavenny;1

They are both excellent writers;

They’ve both recently had short story collections published by Crippen & Landru.

It’s mainly the third of these points that has prompted me to write this week’s post. Tom Mead’s The Indian Rope Trick and Other Violent Entertainments was published at the end of last year and found itself in my pile of Christmas presents. Ethel Lina White’s Blackout and Other Tales of Suspense came out in February, and was part of my birthday book haul. I look forward to seeing what Crippen & Landru have ready for our 15th wedding anniversary in July.

Tom and Ethel are both subgenre specialists, whose output is mostly focussed on a particular style of crime fiction. Mr Mead has been gaining a reputation as a modern master of locked room mysteries and impossible crimes. Ms White was known for her "women in peril” plots, whose protagonists find themselves swept up into less-than-ideal circumstances. The recently published collections are both very good displays of their distinctive styles.

I first encountered Tom Mead’s writing when I randomly picked up Death and the Conjuror in Bridgend library last year (review here). His series detective is retired magician Joseph Spector, who was first introduced in the 2018 short story “The Octagonal Room”. The Indian Rope Trick features Spector’s debut, together with nine other Spector tales and one Spector-free story. Three of these items are previously unpublished, with the others collected from various magazines and anthologies (although, frustratingly, this collection doesn’t include a bibliography with initial publication dates).2

Tom Mead’s influences are not hard to detect. Foremost among these is John Dickson Carr, who Mead has often cited as his favourite author.3 Mead is a passionate and creative heir of Carr’s legacy. The character of an illusionist sleuth was also inspired by the wonderful British television series Jonathan Creek — it wasn’t a surprise from the book’s introduction to learn that Tom Mead was an “enthusiastic young viewer” of the programme. I could actually imagine a few of these stories as the basis for Jonathan Creek plots, especially “Jack Magg’s Jaw” and “The Sleeper of Coldwreath”.4

In his introduction, Martin Edwards quotes the 1941 verdict of Howard Haycraft: “Avoid the Locked Room puzzle. Only a genius can invest it with novelty or interest today.” Sixty-four years later, I guess that makes Tom Mead something of a genius. Even within this short collection, he develops a wide range of impossible crime scenes, including a cable car. There are stories that make fresh use of familiar tropes, with killers who leave no footprints in the snow, or who appear to have been miles away at the time of the murder. As well as the clever puzzles, Tom Mead has a good flair for striking descriptions, of which my favourite was his portrait of Elliot Weblyn as “a pink blancmange in a pinstripe suit.”

Spector’s inaugural case, “The Octagonal Room”, remains one of the strongest in the collection. It opens with a quote from Pierre Louis Maupertuis, who may or may not have spent time in Abergavenny. We’re then introduced to a wonderfully gothic setting: “Rumours about the place have circulated for over a century. Strange meetings and robed figures, bonfires blazing in unoccupied rooms, evil chants echoing through the trees. The mill seems cursed. No villagers venture there.” There is particular mystery around the titular octagonal room, in which a decapitated body is soon found. In the best Carr tradition, the solution is elaborate and artistic.

Another of my favourites was “What Happened to Mathwig”. This begins as an inverted crime story, with the arresting opening line: “If I were not such a gentleman, I would not have agreed to kill Chester Mathwig.” Partway through the story, though, there’s an unexpected twist that draws Spector into the investigation. This twist creates an unusual and enjoyable impossible crime setup.

The collection saves two of the best stories for last, and both are excellent examples of what can be done with just a few pages (7 and 6 pages, respectively). “Lethal Symmetry” is “an account of the strange fate of Conrad Darnoc, who prized symmetry above all things” (note the palindromic name). It has a solution that is both very clever and pleasingly straightforward. Then there’s “Jack Magg’s Jaw”, in which Clive Stoker gathers seven people at his country house to explore his “Museum of Murder”. The denouement brings the anthology to a close with a satisfying final line.

I hope this won’t be the last short-story collection we see from Mr Mead. In the meantime, the fourth instalment of his Joseph Spector series, The House at Devil’s Neck, is available to pre-order. He has also started work on translations of Paul Halter’s impossible crime novels, beginning with The Fourth Door later this year.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (4/5)

I was first introduced to Ethel Lina White through the 2015 British Library collection Silent Nights, which featured her creepy short story “Waxworks”. I have continued to enjoy her appearances in British Library’s anthologies, as well as a number of her novels, and she has definitely become my favourite Welsh fiction writer. Incredibly, Blackout is the first published collection of her stories, appearing 81 years after her death in 1944.

For this collection, Crippen & Landru have brought together 19 of White’s stories. Three of these have been reprinted in the last decade (“Waxworks”, “White Cap”, and “Passengers”), but the rest have been resurrected from various sources first published between 1928 and 1943. The bibliography at the end highlights the value of the anthologising work of Crippen & Landru — Ethel’s output was distributed across a range of publications, from Pearson’s Magazine to Midland Empire Farmer, from The Los Angeles Times to Akron Beacon Journal. In total she wrote over 130 short stories, so I’m hopeful that a sequel will appear soon.

The high quality of her writing becomes even more impressive when you learn about her writing habits. In a letter to her publisher, quoted in the introduction, she summarised her approach thus: “I begin, about twelve, with writing materials, write a few lines, then get a glass of water — another line or so — smoke a cigarette — another line — play with the kitten — and then break for a cup of tea.” My approach to writing sermons is similar, but with eating cheese in place of smoking cigarettes, and watching cat videos instead of playing with a kitten.

As this anthology demonstrates, White was an expert in creating suspenseful situations involving female protagonists, often transforming ordinary domestic settings into tension-filled scenes. In their introduction, Tony Medawar and Alex Csurko describe the main distinctive of her work as “her interest in the psychology of her characters and how it shapes their response to the situations in which they find themselves.” Blackout offers us a pleasing diversity of unsettling situations for characters to respond to — alongside the isolated houses, there’s an underground cave, a factory, a block of flats and city centre housing. We meet women who are just in the wrong place at the wrong time, as well as a hostage, a spy recruit, a few victims of false accusations, and more.

These imperilled women are not monochromatic, but have distinctive temperaments and personalities. Some of the protagonists act foolishly, and you may find yourself shouting at them through the page. Others are more sensible but become caught in a series of unfortunate events. There are also some strong characters, who struggle to persuade others of the validity of their fears, but are eventually vindicated.

In several of the stories, White makes clever use of small details that become unexpectedly significant. This leads to some very satisfying endings, where details from earlier in the story resurface as part of the resolution. It also means some intriguing opening sentence, as with these two examples:

The essential part of this tale is that Ann Shelley was an Oxford M.A.

When Tessa Leigh washed her hair one June evening, she invoked the issue of life or death.

Some of these stories were either expanded into, or became the inspiration for, later novels. Most notably, this includes “Passengers”, the origins of The Wheel Spins (aka The Lady Vanishes). I think Ethel was very wise in repurposing this premise for a novel — the short story form doesn’t give enough space to fully explore the idea, and there is arguably less tension in the shorter version. Among the new-to-me stories, my favourites were probably “Don’t Dream on Midsummer’s Eve”, “The Holiday”, “Mabel’s House”, “White Cap”, and “The First Day”.

The main disappointment with this anthology is the subpar proofreading. Sadly, there are quite a number of typographical and spelling errors. I realise the publisher may be working with limited resources, but perfectionist readers such as myself will find this slightly distressing!

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (4/5)

Writing this means I now have Marty Wilde’s 1958 song, “Abergavenny” stuck in my head. If you’re not familiar with it, you need to click this link and listen to it now, so it can be stuck in your head too.

The original publication details are:

“The Octagonal Room” — Millhaven Tales, 2018

“What Happened to Mathwig” — Wrong Turn (Blunder Woman Productions), 2018

“Invisible Death” — Mystery Weekly, 2018

“Incident at Widow’s Perch” — Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, 2019

“The Indian Rope Trick” — Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, 2020

“The Footless Phantom” — Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, 2022

“Jack Magg’s Jaw” — The Strand Magazine, 2022

“The Sleeper of Coldwreath” — Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, 2023

In one publicity interview for Death and the Conjuror, he said: “It’s a locked room mystery in the tradition of John Dickson Carr (my favourite writer). I’ve done my best to channel everything I love about Carr’s work into my own book. In that respect, it’s a real labour of love.” You can read the full interview here.

I don’t know if it was done consciously or not, but one aspect of “The Sleeper of Coldwreath” very much reminded me of season 4 episode The Chequered Box.

I've enjoyed several of White's novels (The Wheel Spins is, I think, her finest), and I love mystery short stories too, so I'm definitely adding this collection to my list!