Last week, I shared my thoughts about one of the shortlisted books for this year’s H.R.F. Keating Award, an annual prize for the best biographical or critical book related to crime fiction.1 While we’re waiting for tomorrow’s announcement of this year’s winner, it seemed appropriate to write about another of the nominees, which I read at the start of the year but neglected to review for my lovely Substack subscribers.2 As you may have guessed from the title above, the book I’m referring to is the excellent Agatha Christie’s Marple: Expert in Wickedness by Mark Aldridge.

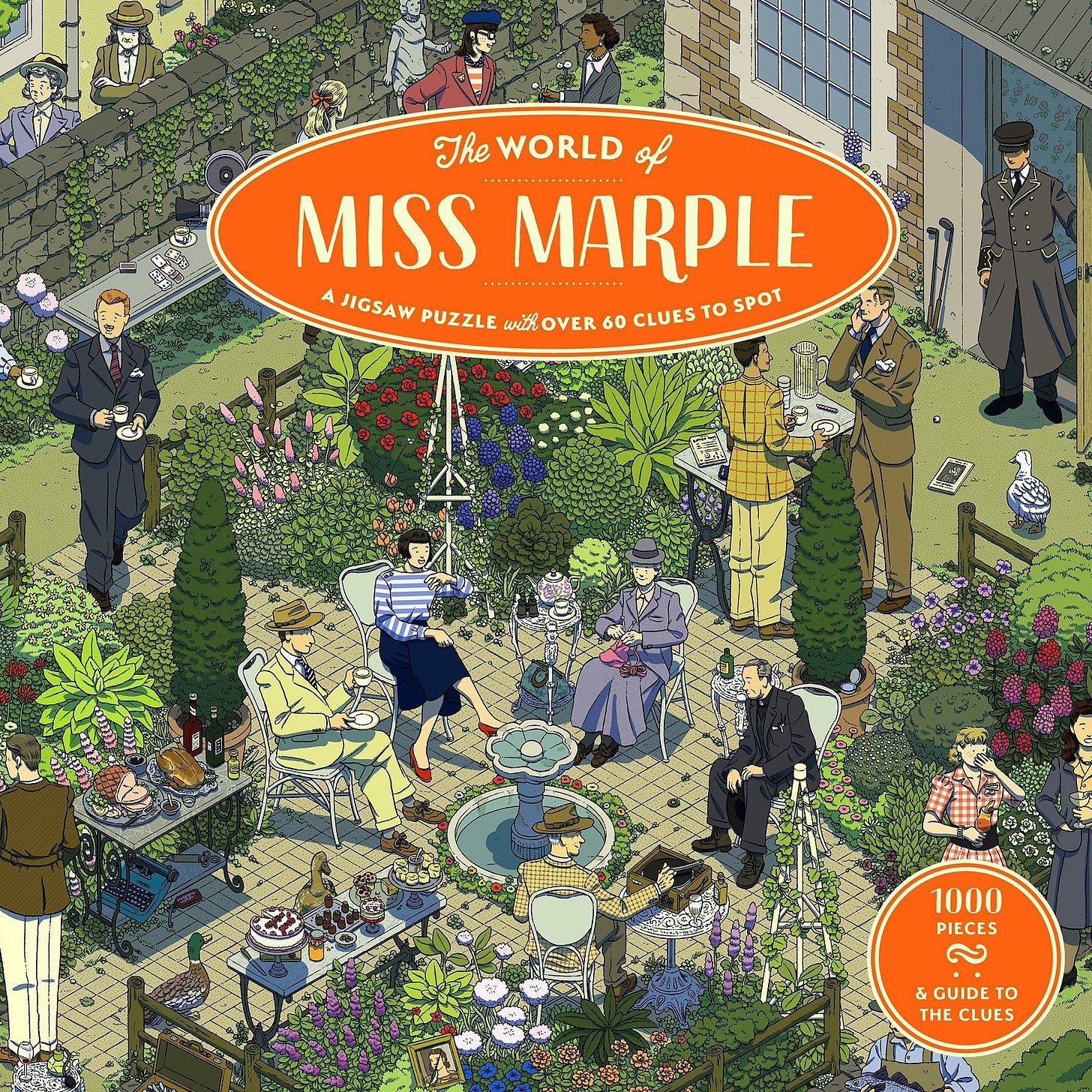

Aldridge’s book is a follow-up to his 2020 book, Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Greatest Detective in the World, which was shortlisted for the 2021 H.R.F. Keating Award. Both books offer fascinating and comprehensive chronological surveys of the literary, theatrical and media careers of Agatha Christie’s two greatest detectives. In Marple’s case, that covers a period from the 1927 short story “The Tuesday Night Club” all the way up to the 2024 official Miss Marple jigsaw puzzle, illustrated by Ilya Milstein. This latter item should give you some idea of just how comprehensive Aldridge’s book is.3

As with its Poirot predecessor, Aldridge has conducted extensive research, with over 800 footnote references to newspapers, books and archival material. At the same time, it’s an obvious labour of love, joyfully written by a passionate Christie devotee, which will make you want to re-read the original books all over again. It is also liberally illustrated, with lots of variant book covers and film posters. Incredibly, Aldridge has managed to avoid significant plot spoilers in the main text, and spoilers are clearly marked as such in the footnotes as well. Even more incredibly for a 400-page book, I only noticed one significant typo.4

In the introduction, Aldridge notes that at the time of Marple’s first appearance, “Agatha Christie’s career was flourishing just as her life seemed to be falling apart,” with the breakdown of her first marriage and her disappearance. Perhaps it’s unsurprising in this context that Christie would develop a new character “whose entire raison d’être was to be a calm point in a stormy sea”.5 Various influences contributed towards Marple’s creation, including Christie’s experience depicting Caroline in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd—“an acidulated spinster, full of curiosity, knowing everything, hearing everything.”6

In terms of the canonical novels, Aldridge’s book is particularly valuable for how it situates Christie’s writing within her life story and the wider context of world events. It’s easy to forget, for example, the impact of the war on the publishing industry, Christie’s books included. The impact of Christie’s wrist injury on the writing of A Pocket Full of Rye provides a good reminder of the author’s humanness. As another example, the author’s dictaphone usage later in life helps to explain some of the shortcomings of certain books. The details of magazine serialisations are always interesting, when we’re now so familiar with the stories in their final novel form. Thanks to surviving typescripts and notebooks, we also have some insights into Christie’s redrafting and editing processes.

One of the most fascinating aspects of both of Aldridge’s character surveys is reading about the author’s attitude towards film and television adaptations of her novels. As with Poirot, she had serious reservations about Marple adaptations and, later in life, expressed some regrets. In terms of radio, Christie was content for the BBC to broadcast straight readings of her stories, but only authorised one full-cast adaptation. This was the short story “Death by Drowning”, which she unsuccessfully attempted to prohibit the BBC from repeating the following year.7 She was also retrospectively critical of theatrical adaptations. Interestingly, she was critical not for their deviations from her work but for their misguided attempts at fidelity:

“It seemed to me that the adaptations of my books to the stage failed mainly because they stuck far too closely to the original book. A detective story is particularly unlike a play, and so is far more difficult to adapt than an ordinary book.”8

Her worst experiences with adaptations, though, came from the world of film. When MGM decided to place Marple in an original screenplay for 1964’s Murder Ahoy, Christie wrote a “devastating” letter to producer Lawrence Bachmann, with the opening line “soft words butter no parsnips”:

“I do not see how you can expect me to feel anything but deep resentment at your high handed action, or to pretend otherwise, and I still feel it questionable that you really have the right to act as you have done.”9

On a different topic, one aspect of Golden Age detective fiction which I find increasingly interesting is its incidental commentary on the use of capital punishment, which was abolished in the UK in 1965.10 This appears at a few points in Aldridge’s survey. In The Murder at the Vicarage (1930), one resident remarks: “We think with horror now of the days when we burnt witches. I believe the day will come when we will shudder to think that we ever hanged criminals.” Contrastingly, in 4.50 from Paddington (1957), Miss Marple remarks: “I am really very, very sorry that they have abolished capital punishment because I do feel that if there is anyone who ought to hang it’s [name redacted].” With these comments, Christie seems to be anticipating the abolition of the death penalty, which was still a legal punishment at the time. Marple’s words reflect Christie’s own comments in her Autobiography, where she asks of a hypothetical young murderer: “Why should they not execute him? We have taken the lives of wolves in this country…”11

There are a huge number of fascinating bits of trivia throughout, including these that have stuck in my mind:

Evening Standard critic George Malcolm Thomson caused controversy when his review of A Murder is Announced revealed the murderer’s identity. Responding to his detractors, he wrote: “The detective writers who have rushed to the support of Agatha Christie should keep their muddled reasoning for their novels.”12

Christie changed her mind a number of times about the departure time and station for 4.50 from Paddington, at one point suggesting the station should be called Padderloo (a mix of Paddington and Waterloo), “just in case a resident of a large country estate half-an-hour from Paddington should be upset about being implicated in the fictional crime.”13

J. R. R. Tolkien was inspired to stay at Brown’s Hotel in Mayfair after reading At Bertram’s Hotel. During his stay, “he encountered his own mystery: the sound of footsteps in the corridor. Deciding to investigate, he then found himself locked out of his room.”14

In the final pages of the book, Aldridge investigates how the character of Miss Marple has been explored and developed through various adaptations and fresh works, including the Japanese anime series Agatha Christie’s Great Detectives Poirot and Marple and the 2022 short story collection Marple. He closes with a quote from Christie’s great-grandson James Prichard, who expresses a desire to see Miss Marple in a new visual production: “Whether that’s in TV or film, that’s a debate, but I think Marple deserves that kind of treatment. She needs her moment.” I guess we can expect a revised and expanded edition of Aldridge’s book sometime soon, then.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

The full list of nominees, which all sound fascinating, is:

Mark Aldridge for Agatha Christie’s Marple: Expert in Wickedness

Jem Bloomfield for Allusion in Detective Fiction

Ashley Bowden for Female Detectives in Early Crime Fiction 1841-1920

Dan Coxon & Richard V. Hirst for Writing the Murder: Essays in Crafting Crime Fiction

Sara Lodge for The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female

Lynda La Plante for Getting Away With Murder: My Unexpected Life on Page, Stage and Screen

You can see a list of past winners, and the nominees for other awards at the CrimeFest website.

I am not, of course, assuming that all of my Substack subscribers are lovely, but it is the lovely ones I have in mind when I write a post.

Similarly, Christie fans will be pleased to note that the volume on Poirot is comprehensive enough to include the detective’s appearance in the timeless 1997 Spice Girls film Spice World, played by Hugh Laurie.

On page 330, Joan Hickson is quoted as saying: “The BBC had already pencilled the remaining one into their filming schedule, assuming I would do it. But they rather jumun.” My wife and I spent a good while trying to work out if jumun was a slang term and what it could mean. Eventually, I resorted to making contact with Mark Aldridge, who kindly responded to my query to clarify that it should read: “They rather jumped the gun.” Something went awry when a picture was inserted after the final text was signed off.

Page 2.

Page 5, quoted from her Autobiography.

Details of the background and recording is covered on pages 130—132.

Quoted on page 84. The quote is from her Autobiography.

Quoted in page 215.

Strictly speaking, capital punishment was not fully abolished at this point, as the death penalty remained in place for certain offences for a long time afterwards. In my childhood, I remember visiting the gallows at the Royal Navy base in Plymouth, when it could theoretically still be used for executions.

She concludes: “What one can do with a killer? Not imprisonment for life — that surely is far more cruel than the cup of hemlock in ancient Greece. The best answer we ever found, I suspect, was transportation. A vast land of emptiness, peopled only with primitive human beings, where man could live in simpler surroundings. “

Page 102.

Page 147.

Page 226.