Like most readers of this Substack, I visit multiple bookshops every year. New bookshops, old bookshops, charity bookshops, children’s bookshops, bookshops with cafes, bookshops with spiders. In all of my bookshop adventures, though, I have yet to come across a bookshop with a dead body betwixt the shelving. In the world of fiction, however, bookshops can be dangerous places, as I have recently discovered from two vintage mysteries in the British Library Crime Classics series.1

These are examples of the crime subgenre of “bibliomysteries”. If you’re not familiar with the word, I’ll let Otto Penzler explain:

“If much of the action is set in a bookshop or a library, it is a bibliomystery, just as it is if a major character is a bookseller or a librarian. A collector of rare books… may be included. Publishers? Yes, if their jobs are integral to the plot. Authors? Tricky… If the nature of their work brings them into a mystery, or their books are a vital clue in the solution, they probably make the cut.”2

In other words, if you like books and you like fictional murders, you’ve come to the right place.

First published in 1956, Death of a Bookseller tells the story of the death of a bookseller.3 The bookseller in question is Mike Fisk, who has recently introduced Sergeant Wigan to the world of rare book collecting. An obvious suspect is soon arrested, but Sergeant Wigan has his doubts and insists on investigating further.

Bernard Farmer drew on his life experience to write this novel: he was both a former Metropolitan police officer and a book collector with an interest in first editions. In fact, in 1950 he published The Gentle Art of Book Collecting, with chapters including “Why an author is collected”, “How to tell a first edition” and “Old Bibles”. He was a particular aficionado of G. A. Henty, who is also highly sought-after in the fictional world of Death of a Bookseller. This was his second crime novel, following 1953’s Death at the Cascades. It was followed by Once, and Then the Funeral (1958) and Murder Next Year (1959). All featured Sergeant Wigan.

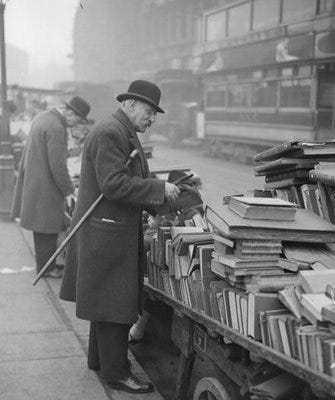

Farmer’s bibliophilic passion brings a great sense of authenticity to the book. I especially enjoyed the portrayals of different personalities in the book trade, including his description of the world of “book runners”, who browse bookshop stock in hopes of finding bargains that they can sell elsewhere. We meet Charlie Boy, who had a wheelbarrow of books, but also “a small stock of valuable volumes which might have astonished the pundits of the trade who affected to despise him”. Then there’s Ruth Brent, who ruthlessly acquires first editions for a wealthy American collector. And there’s Fred Hampton, “an excitable man, and violent when he thinks he can get away with it.”

The characters are definitely the best thing about the book; the plot itself is less engaging. Bernard Farmer gives us a strong opening, leading us at a good pace through the initial scenes. Somewhere after the halfway point, though, the investigation becomes significantly less interesting. The “race against time” element of the plot, with Wigan attempting to find evidence to free the accused, adds a bit of extra colour, but not enough to lift my verdict above “good”. I’d still recommend it to bibliophiles, but for the characterisations rather than the investigation.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐ (3/5)

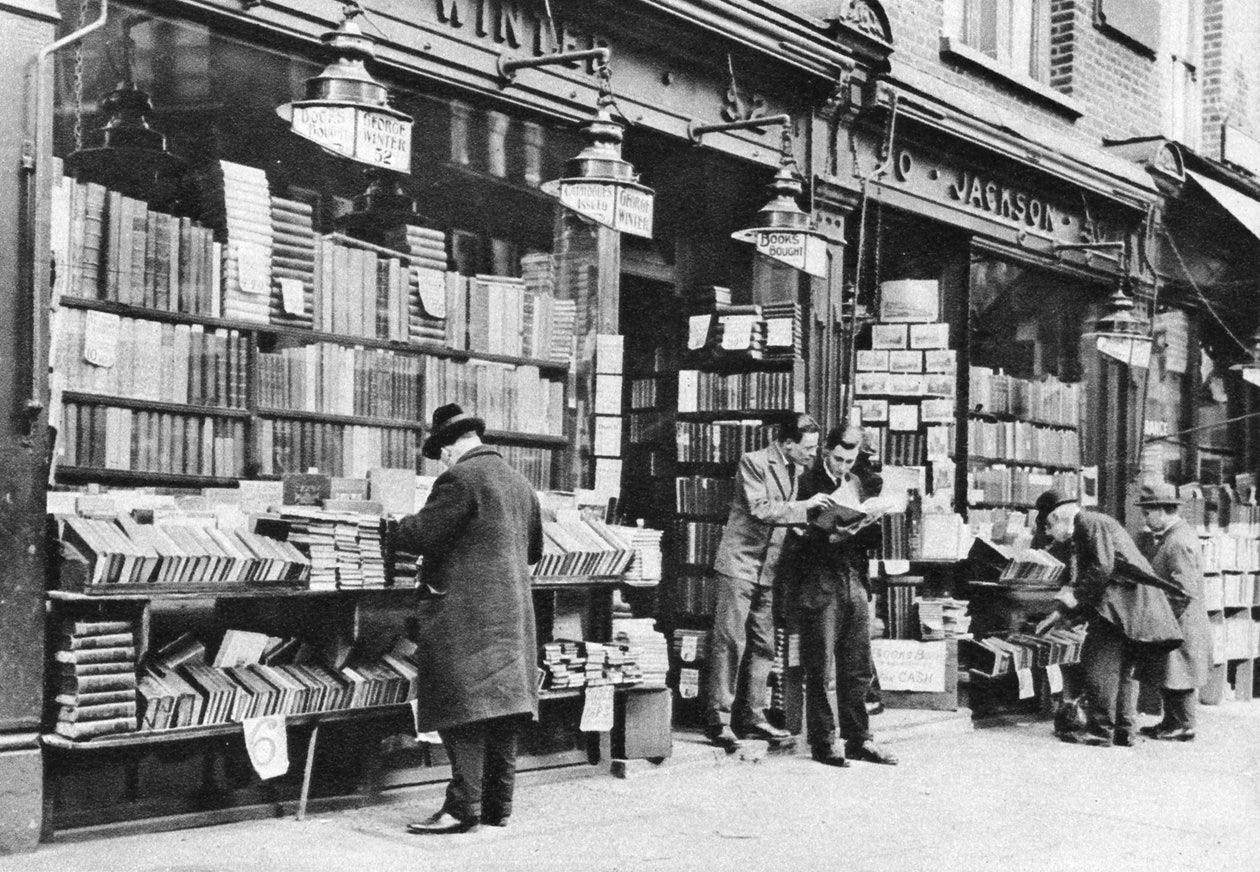

John Ferguson’s Death of Mr Dodsley (1937) is set in a more familiar bookselling environment, as the titular Mr Dodsley owned a bookshop on Charing Cross Road. Sadly, his tenure came to an end when his dead body was discovered on the premises. His fellow dealers (who harboured an envy of Dodsley’s stock) assumed “that he had shot himself in a moment of depression, an act which they could quite understand, for things were very bad just then in the second-hand book business.” In reality, he had been murdered, launching an investigation that encompasses Charing Cross Road, the House of Commons, and Lymington.

John Ferguson was a Scottish clergyman, joining fellow ministers Father Ronald Knox and Canon Victor Whitechurch in the world of classic crime writing.4 He began writing thrillers while working as a school chaplain at Eversley girls' school in Sandgate, Kent, publishing Stealthy Terror in 1918. Ten years later, he introduced his series sleuth, Scottish private detective Francis MacNab, in The Man in the Dark. MacNab appeared in four further novels, Death of Mr Dodsley being the last.

I very much enjoyed the opening of this novel. After an unlabelled floorplan of the bookshop, we find ourselves in an all-night sitting at the House of Commons. At the House, we’re also introduced to a newly-released crime novel, Death at the Desk, which plays an important role in the following narrative. The next chapter then takes us to Charing Cross Road, where Constable Roberts is on patrol, encountering a drunk man who talks apparent nonsense about a door and a cat. Eventually, this encounter leads the constable to the scene of the crime.

Private detective Francis MacNab is drawn into the case alongside the official investigators Crabb and Mallett (who is not a fan of detective stories).5 As the investigation continues, there is some interesting interplay between Scotland Yard and MacNab, with debate over the guilt or otherwise of an apparently obvious suspect. According to Golden Age convention, we might assume that MacNab’s position will be vindicated, but that assumption is questioned by new perspectives on clues.

Although there were enjoyable parts to this mystery, overall I came away disappointed, feeling that a lot of the novel’s potential was unrealised. It ended up being quite hard work to get through. There were some interesting characterisations, but MacNab himself is a fairly forgettable sleuth. The plot seemed to lose momentum partway through, and some of the investigation was frustratingly facile (e.g. a broken watch apparently fixing the time of the murder). Hopefully the Rev Ferguson’s sermons were more engaging.

Verdict: ⭐⭐ (2/5)

For a full list of British Library Crime Classics books that I’ve read and reviewed, see my BLCC page here.

I say “recently” — I’m catching up on reviews from the end of last year.

Quoted in Martin Edwards’ introduction to the 2022 short story collection Murder By The Book. You can read the introduction on Crime Reads here: https://crimereads.com/a-deep-dive-into-the-history-of-bibliomysteries.

There is a more recent Death of a Bookseller by Alice Slater (published 2023), which is also about the death of a bookseller.

In his 1931 history of the genre, Masters of Mystery, H. Douglas Thomson commented on ecclesiastical detective fiction authors: “The Presbyterians have been strangely silent, and we have yet to welcome the advent of a Calvinistic detective” (page 241).

“Ah Crabb,” he said with a sigh, “this is what comes of reading detective stories. No plot is too far-fetched for that type of fiction. Give ‘em up, Crabb: it’s a bad habit that may ruin your career.” (page 164 of the BLCC edition).

I love the mission of the British Library Crime Classics so much that I’m hesitant to say anything negative about the series, but I find it to be very hit or miss. For every delightful forgotten gem, I find one or two duds that just don’t work. I haven’t read either of these yet, but based on your reviews I’ll probably pass them by…