A month ago, I saw a review on FictionFan’s blog for a vintage crime novel set in the Welsh valleys in the 1920s, and immediately knew I had to read it. The novel in question was Menna Gallie’s Strike for a Kingdom (1959), which I hadn’t previously heard of. Thankfully, our local public library have a copy in their reserve stock, which had remained unread for 6 years. I promptly requested it, and discovered a new addition to my list of favourite Welsh novels.1

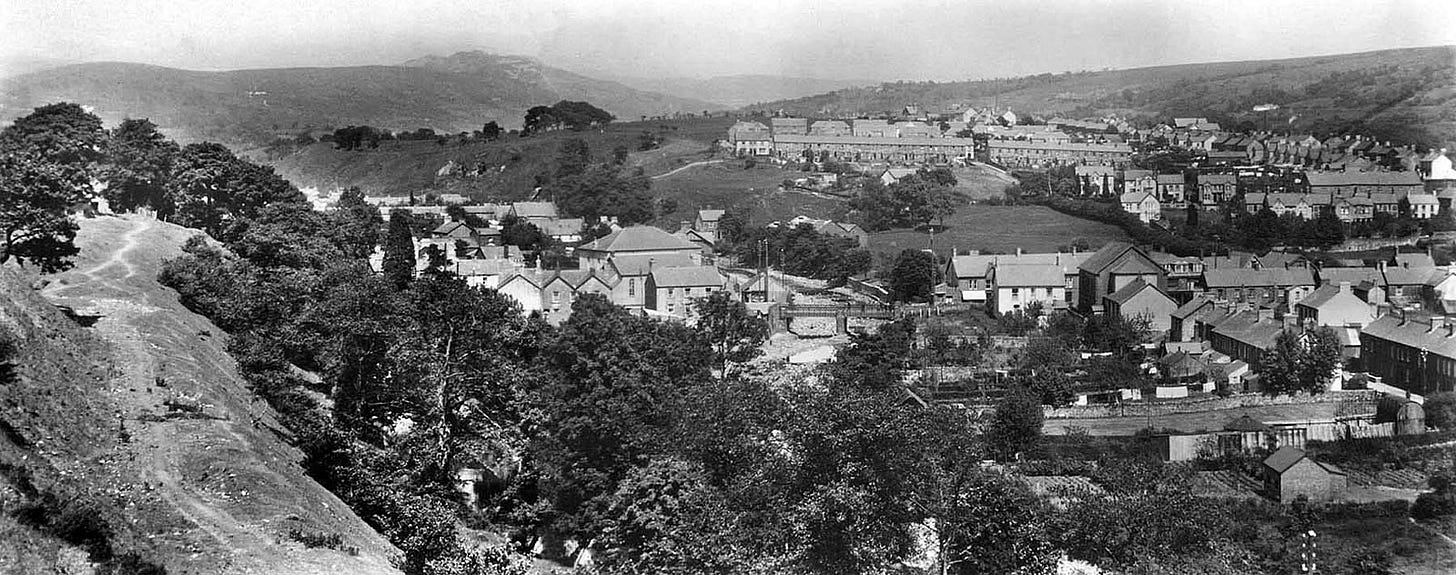

Menna Gallie grew up just 20 miles from my home in Bridgend, in the mining town of Ystradgynlais.2 She was from a Welsh-speaking family, and didn’t learn English until the age of eight. When she turned to novel-writing in her 30s, though, she decided to write in English. At the time, she was living in Northern Ireland, working as a part-time teacher at Orangefield Boys' Secondary School, where she may have taught Van Morrison.3

Strike for a Kingdom was Menna Gallie’s first novel, which she hid in a drawer for over a year before her husband persuaded her to submit it to a publisher. This proved to be a very wise move: Gollancz saw the book’s value, and encouraged her to continue writing, publishing five of her novels in total. The book was well-reviewed in both the UK and the US. It was even praised by Eleanor Roosevelt, who described it as “charmingly written with feeling and depth of understanding.”4 In the UK, it was nominated for the 1959 Crime Writers' Association Gold Dagger Award (then known as the Crossed Red Herring Award), losing out to Eric Ambler’s Passage of Arms. Its fortunes were revived in 2003, when Welsh women’s publisher Honno reprinted it.5 BBC Radio 4 also broadcast a dramatisation in 2012.6

Strike for a Kingdom is set in the Tawe Valley during the 1926 miners’ strike. We are introduced to the fictional mining community of Cilhendre, “a little huddle of pigeon-coloured houses following the curves of the River Tawe, which plaited its way among them, with the road and railway for company.” The strikers and their families have come together in solidarity—and in fancy dress—for a carnival (“a bit of a spree, like, to cheer us up”). During the carnival, the much-hated mine manager is discovered dead in the river. There are many people with a possible motive, but uncovering the truth will not be straightforward.

There are two contrasting characters taking an investigative role, both convincingly depicted. The first is D.J. “Davy” Williams, who has to wrestle with competing loyalties as both a Justice of the Peace and a miner on strike. At one point, he ends up in a police cell after joining a march with other colliers, but he also recognises his responsibility to implement justice:

The enemy, the symbol was destroyed; but someone would be called to answer for it—someone he knew, almost certainly… Thou shalt not kill. Yes, yes, I know, but thou shalt not oppress either, nor bully, nor threaten, nor covet and get thy neighbour’s wife.

In contrast to the affable Davy, Gallie introduces us to Inspector Evans. An outsider to Cilhendre, he is unsympathetic to the miners’ cause and sees himself as part of a superior class of men. Like many of his contemporaries, he is a Welsh speaker but “preferred not to let it be known that he suffered from this disability.” He becomes frustrated by the closeness of Cilhendre’s community, where people create false alibis and misleading stories to protect each other. Even the widow is not entirely cooperative: “Will you allow my affairs to be turned over in public by every Tom, Dick and Harry, like—like women turning over second-hand clothing in a market-place?”

The book’s descriptions have a definite sense of authenticity, with various autobiographical influences. Menna Gallie had lived through the 1926 strike, and the novel reflects the socialist convictions she developed through her upbringing and childhood experiences.7 Her insights into chapel culture doubtless come from her own chapel attendance, where psalm singing was apparently more common than it is now. The character of D.J. Williams is based on her uncle, W.R. Williams, who shared his fictional counterpart’s professions, interests and politics.8 The fabricated setting of Cilhendre (which also featured in The Small Mine in 1962) is based on the village of Ystalyfera, near her birthplace.9 (In later life, she and her husband gave the name “Cilhendre” to their house in Pembrokeshire, where there’s now a commemorative slate plaque on the wall.)10 Gallie also returns to her native tongue in the book, with periodic uses of Welsh and Wenglish.11

There is an enjoyable seam of humour running through the narrative, in the descriptions, conversations and character interactions. I could cite as an example the dialogue between two maids when they discover their master is dead, and one says: “I’d hate to be dead, wouldn’t you? Specially summertime.” And then there’s the miner who complains about his wife’s religiosity: “She goes down to that chapel in Clydach and comes home with diarrhoea and messages.”12 In Gallie’s unique style, this humour is sharply juxtaposed with more serious and tragic scenes. One reference work sums up her writing with a description that is definitely apt for Strike for a Kingdom:

“She has an exuberant prose-style and an inventive comic flair but, although humorous, she cannot be called a comic writer since comedy tends to go with seriousness and pathos in her work, resulting in a bitter-sweet amalgam.”13

I realise I haven’t yet commented on the mystery itself. In his review, Julian Symons praised the book, but commented: “The puzzle is no more than adequate.”14 I think I agree with Symons — from the perspective of clues and detection, the book is average, but as an overall crime novel, Gallie’s writing puts this in the category of “excellent” (or “ardderchog”). In the hands of a less competent writer, the mystery may have lacked interest, but her prose, humour and exploration of community dynamics make this a very engaging investigation. The ending is also ardderchog, with the mystery leading to an explosive climax, followed by a lighter scene to clear up one loose end, and then a satisfying “life goes on” paragraph. It’s an enjoyable read from start to finish, and especially if you have Welsh connections.

Finally, as a parent in Wales with young children, I should comment on my appreciation of the reference to the song “Sospan Fach”, which is played at the carnival. Children still joyfully learn this folk song today, despite the slightly bizarre words, which translate to:

Mary-Ann has hurt her finger,

And David the servant is not well.

The baby in the cradle is crying,

And the cat has scratched little Johnny.

A little saucepan is boiling on the fire,

A big saucepan is boiling on the floor,

And the cat has scratched little Johnny.

Poor little Johnny.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (5/5)

My favourite Welsh author is definitely Ethel Lina White, and Some Must Watch would probably top the list of her novels that I’ve read so far. My favourite novel set in Wales by a non-Welsh author is Murder of My Aunt by Richard Hull. If you want a good collection of Welsh and Welsh-themed short stories, the British Library anthology Crimes of Cymru is excellent.

Most of this biographical information comes from her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, written by Angela V. John. If you have access, you can read it here: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/98305.

Van Morrison attended Orangefield in the 1950s, leaving without any qualifications in 1960. So, he was there at the same time as Menna Gallie, but I have no other evidence that she actually taught him.

Quoted in an advertisement in The Atlantic, February 1960.

The library’s copy, though, was the original 1959 Gollancz printing, which is fun.

I would love to hear a recording of this, if anyone can find it!

In the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, John P. Jenkins writes: “Although Menna Gallie's father was not a miner, and therefore not directly affected by the 1926 strike, it had a profound effect on her politics. Her liminal position at her primary school, where she was among hungry strikers' children but whose suffering she could not fully share because she had no need of the communal meals served to them, generated a 'guiltless guilt' which she expiated in her first novel Strike for a Kingdom (1959).”

See the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry.

Katie Gramich, Twentieth-Century Women's Writing in Wales (University of Wales, 2007), page 125.

Wenglish is a way of describing Welsh dialects of English, especially spoken in the south Wales valleys.

I have preached a few times at a chapel in Clydach, but did not come home with diarrhoea on any of those occasions.

From her entry in the Oxford Companion to the Literature of Wales (Oxford University Press, 1986), page 208. Katie Gramich similarly writes: “This convergence of potentially tragic subject-matter with a robust comic style is highly characteristic of Gallie’s work and contributes to making her novels slightly uneasy reading — there can be a modulation from the humorous to the heart-rending within the space of one paragraph.” (Twentieth-Century Women's Writing in Wales, page 126).

From his “Criminal Column” in The Sunday Times, 15 February 1959. In the same column, he reviewed Joan Fleming’s Malice Matrimonial, Anthony Gilbert’s Third Crime Lucky and Frances Duncombe’s Death of a Spinster.