This is the fourth instalment of my year-by-year crime journey through the 20th century (you can read the previous instalments here). In this tranche of mysteries, we meet three significant characters in the history of crime fiction: the gentleman burglar Arsène Lupin, the French detective Inspector Hanaud, and the medical jurispractitioner Dr Thorndyke. Two of these, and their creators, were new to me, whereas the third is a familiar friend.

As well as being in chronological order, today’s reviews happen to be in ascending order of quality, from the mediocrity of 1909 to the enjoyability of 1911.

Like many others, I was introduced to the character of Arsène Lupin by the modern Netflix series Lupin, which follows the exploits of Lupin devotee Assane Diop.1 Conceived in 1905 by French writer Maurice Leblanc, Arsène Lupin is a master of disguise and a gentleman burglar, in a similar vein to E. W. Hornung’s Raffles. In the words of Melvyn Barnes, “he is a thief, but basically a decent enough chap.”2 His fictional rival is Sherlock Holmes, who is subtly disguised in the Lupin stories under the aliases Herlock Sholmès or Holmlock Shears.

After appearing in two short story collections, Arsène Lupin had his stage debut in 1908 with the inventively-named four-act play Arsène Lupin. The following year, the play was novelised by Edgar Jepson, under the title Arsène Lupin. This novel was the 1909 choice for my through-the-century reading challenge.

The play/novel opens with a happy millionaire, M. Gournay-Martin, whose daughter Germaine has announced her engagement to the Duke of Charmerace. The celebrations, though, have been marred by the arrival of a letter signed ARSENE LUPIN. The letter-writer itemises various valuable possessions owned by M. Gournay-Martin, including a coronet, and requests their owner sends them addressed to Lupin at a railway station. And if the request is ignored? “I shall proceed to remove them myself on the night of Thursday, August 7th.”

The ensuing narrative is completely predictable, and the shocking final twist can be seen at a distance of at least 100 pages. It also seems that not much thought was put into adapting the play into a novel, as the prose is essentially a theatre transcript, consisting almost entirely of dialogue. There are some fun moments, and some of the dialogue is enjoyable, but this definitely isn’t a good showcase for either Leblanc or Lupin. I imagine the short stories are better; I’ll aim to explore them one day.

Verdict: ⭐⭐ (2/5)

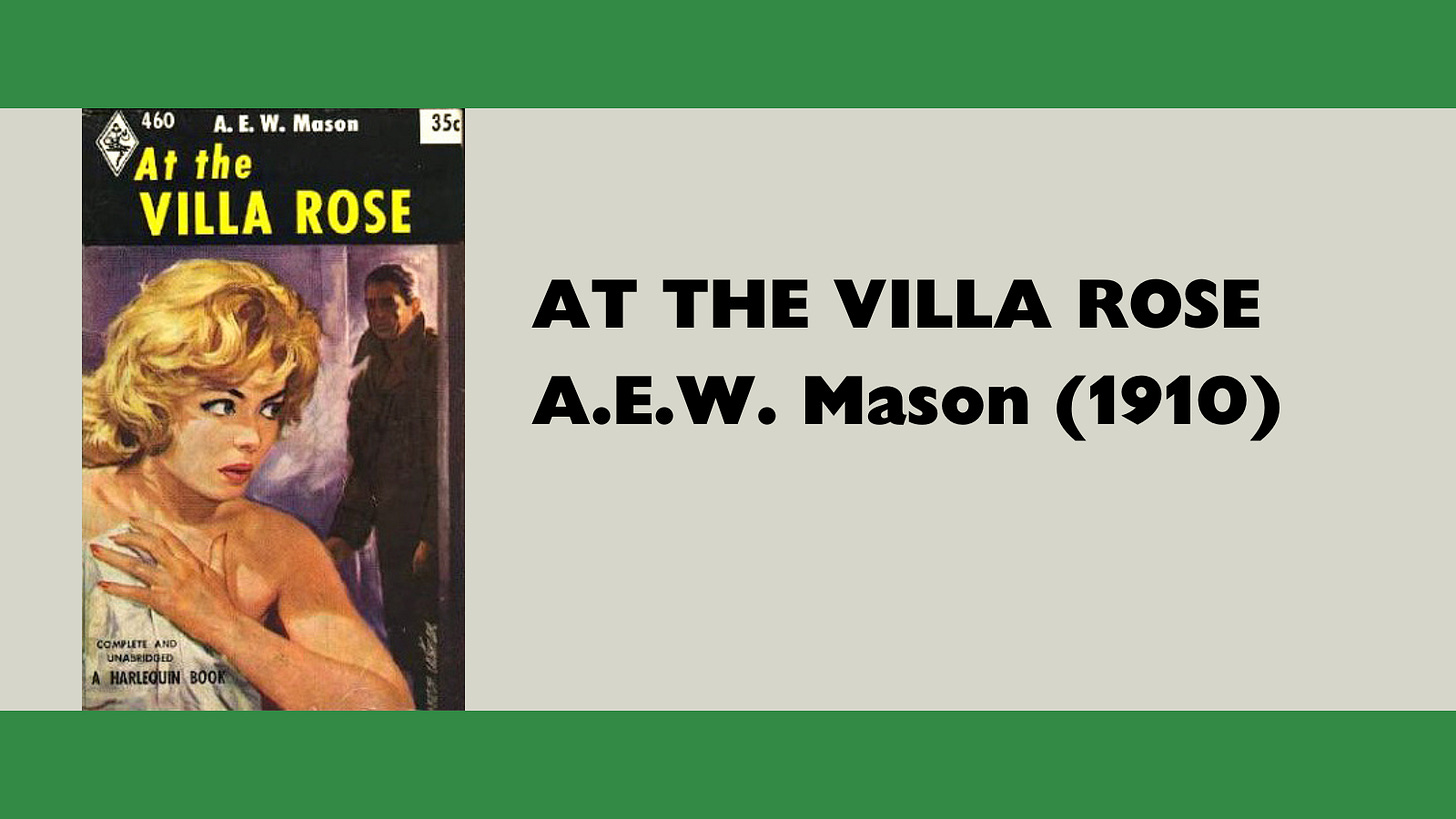

It’s summertime in Aix-les-Bains, and Mme Dauvray has been strangled to death. Some of her jewels have also been stolen and her maid Hélène is found tied up and unconscious. Her companion and personal séance-provider Celia has disappeared — and thus becomes the number one suspect. Celia’s man friend, Harry Wethermill, believes she is innocent, and persuades Inspector Hanaud to investigate, assisted by Julius Ricardo in the “Watson” role.

At the Villa Rose is the inaugural outing for Inspector Hanaud, who appeared in four further novels. His creator, Albert Edward Woodley Mason, was already an accomplished novelist, with 12 previous books to his name, including the popular 1902 adventure story The Four Feathers. Martin Edwards has described him as “a Renaissance man if there ever was one… an actor, cricketer, MP, spy and playwright.”3

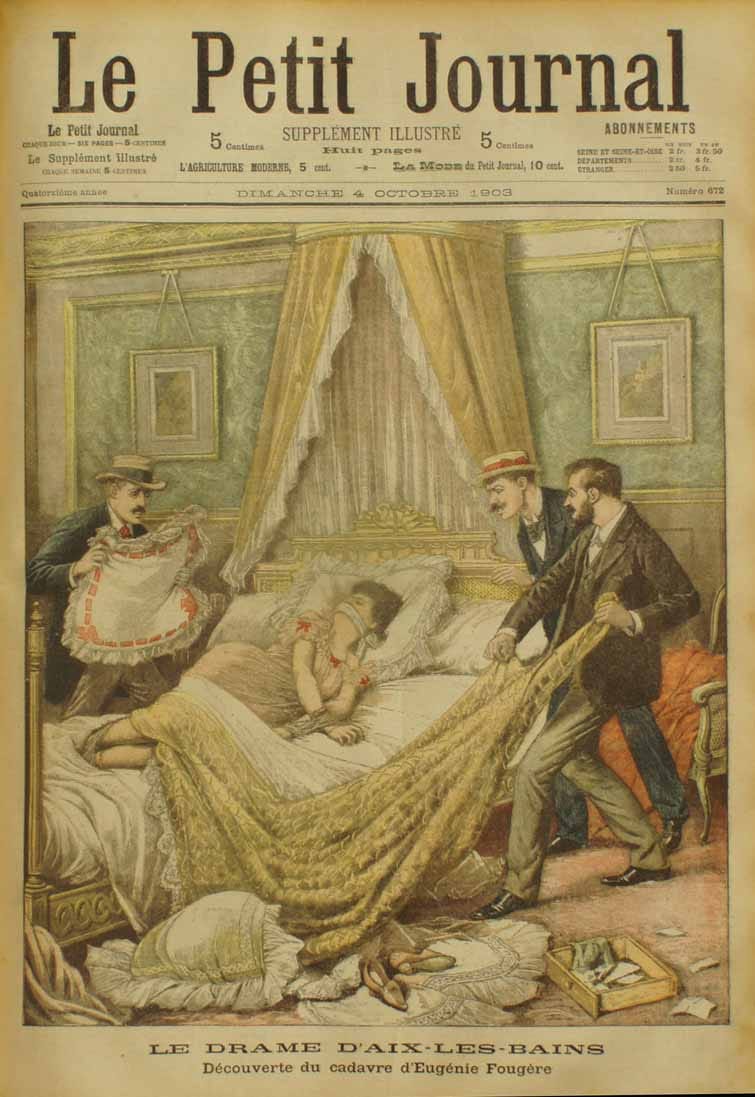

For this novel, A.E.W. Mason was inspired by a number of real-life events. The initial inspiration came from learning about the case of Eugénie Fougère, who was murdered along with one of her female servants in 1903.4 He further developed his ideas while attending a murder trial at the Old Bailey, in which someone was convicted of killing a newspaper shop owner. The character of Inspector Hanaud found its origins in the memoirs of Marie-François Goron and Gustave Macé, heads of the Paris Sûreté. The aim, in Mason’s words, was to create a detective who was “as physically unlike Mr. Sherlock Holmes as he could possibly be."5

At the Villa Rose is not a typical whodunnit, in that the question of whodunnit is resolved fairly early on. With this approach, the author was aiming to combine “the crime story which produces a shiver with the detective story which aims at a surprise” — in this case, the “surprise” appearing in the middle rather than at the traditional end of the book.6 I’m not convinced that the long explanation that follows delivers the “shivers” that Mason was hoping for. I found the first half of the novel significantly more engaging than the second. Even so, there is a good mystery here, with some clever misdirection and some enjoyable characterisations.

"For a cumbersome man he is extraordinarily active," said Mr. Ricardo to Harry Wethermill, trying to laugh, without much success. "A heavy, clever, middle-aged man, liable to become a little gutter-boy at a moment's notice."

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐ (3/5)

Unlike most of the other authors whose works I’ve read for my 100-year journey so far, R. Austin Freeman is a writer I’m already familiar with. I’ve enjoyed a number of his Dr Thorndyke novels, my top picks currently being The Mystery of Angelina Frood, Mr Pottermack’s Oversight, and For the Defence: Dr Thorndyke. I’m glad that I can now add The Eye of Osiris to this distinguished list of Freeman Favourites.

This is the second novel featuring Freeman’s prolific series detective Dr John Thorndyke, an expert in medical jurisprudence who applies his scientific wisdom to criminal conundrums. In this case, he investigates the disappearance of Egyptologist John Bellingham. The fate of Mr Bellingham becomes an even more serious question after a “horrible discovery in a watercress-bed” and the subsequent appearance of additional human remains. There’s also an extra layer of complexity arising from the slightly bizarre provisions of Bellingham’s will.

I don’t think any reader will be surprised to learn about the author’s medical background, which included a stint working as a doctor at Holloway Prison. Freeman’s professional experience is seen most clearly in his concern for forensic authenticity. He saw the main appeal of detective stories lying in the “how” rather than the “who”, which led him to pioneer the subgenre of inverted mysteries, where the culprit is known from the beginning. According to Who’s Who, his hobbies included modelling in clay and wax, which is one way of passing the time I suppose.7

I recognise that Freeman’s meticulous concern for detail, and the resulting slow pace of investigation, is not to everyone’s tastes. Personally, I enjoy his writing style, and The Eye of Osiris is a very good showcase of his talents.8 The prose is both engaging and entertaining, with many wonderfully wry comments as well as a surprising number of laugh-out-loud moments.

‘What a magnificent onion, Miss Oman! and how generous of you to offer it to me—’

‘I wasn’t offering it to you. But there! Isn’t it just like a man—’

‘Isn’t what just like a man?’ I interrupted. ‘If you mean the onion—’

‘I don’t!’ she snapped; ‘and I wish you wouldn’t talk such a parcel of nonsense.’

I also think Freeman would have made a good restaurant critic, introducing us to one eatery “whereof the atmosphere was pervaded by an appetising meatiness mingled with less agreeable suggestions of the destructive distillation of fat.” The actual plot is strong too, with an especially satisfying resolution to the contested will. I have several more Thorndykes on the shelf, and look forward to reading them.

Verdict: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (4/5)

My next reads will be The Chink in the Armour by Marie Belloc Lowndes (1912), The Grell Mystery by Frank Froest (1913) and The Four Faces by William Le Queux (1914). I’m hoping to make it into the 1920s by the end of the year!

My quick review of the Netflix series: Part 1 was enjoyable, Part 2 was disappointing, Part 3 was somewhere between the two.

Melvyn Barnes, Best Detective Fiction (1975), 32.

Martin Edwards, The Life of Crime (2022), 101.

You can read a contemporary New York Times article about the case here. On the same page, you’ll also find a fascinating piece about the trapping of eels.

From the preface in the 1931 omnibus Inspector Hanaud’s Investigations (published by Hodder and Stoughton).

As explained in the 1931 omnibus preface.

The Who’s Who entry is quoted in H. Douglas Thomson, Masters of Mystery (1931), page 169.

Some of his novels are, I concede, fairly dull. The Cat’s Eye is one example of Freeman’s ability to remove any sense of drama from high-drama situations.

Thanks for the reminder of authors I'd liked and forgotten like A E W Mason. Love reading your postings! I've just 'discovered' H C Bailey's Mr. Fortune short stories. Marvelously done.

This is such a cool project! Can’t wait for the next installment.